Letters to Vera, Walt Whitman, Vita Sackville-West, and more...

As some of us go or recently went into lockdown 2.0, let’s remind ourselves that this is not going to last forever and in fact, the end of the pandemic is now in sight. Scroll on for some inspiration for your holiday cards and notes to friends and family, from correspondence between some of your dearest artists and writers

First, some excerpts from the letters between Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West (warning: you might melt)

From Sackville-West to Woolf

Milan [posted in Trieste]

Thursday, January 21, 1926I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia. I composed a beautiful letter to you in the sleepless nightmare hours of the night, and it has all gone: I just miss you, in a quite simple desperate human way. You, with all your un-dumb letters, would never write so elementary phrase as that; perhaps you wouldn’t even feel it. And yet I believe you’ll be sensible of a little gap. But you’d clothe it in so exquisite a phrase that it would lose a little of its reality. Whereas with me it is quite stark: I miss you even more than I could have believed; and I was prepared to miss you a good deal. So this letter is just really a squeal of pain. It is incredible how essential to me you have become. I suppose you are accustomed to people saying these things. Damn you, spoilt creature; I shan’t make you love me any the more by giving myself away like this—But oh my dear, I can’t be clever and stand-offish with you: I love you too much for that. Too truly. You have no idea how stand-offish I can be with people I don’t love. I have brought it to a fine art. But you have broken down my defences. And I don’t really resent it …

Please forgive me for writing such a miserable letter.

V.

*

From Woolf to Sackville-West

52 Tavistock Square

Tuesday, January 26Your letter from Trieste came this morning—But why do you think I don’t feel, or that I make phrases? ‘Lovely phrases’ you say which rob things of reality. Just the opposite. Always, always, always I try to say what I feel. Will you then believe that after you went last Tuesday—exactly a week ago—out I went into the slums of Bloomsbury, to find a barrel organ. But it did not make me cheerful … And ever since, nothing important has happened—Somehow its dull and damp. I have been dull; I have missed you. I do miss you. I shall miss you. And if you don’t believe it, you’re a longeared owl and ass. Lovely phrases? …

But of course (to return to your letter) I always knew about your standoffishness. Only I said to myself, I insist upon kindness. With this aim in view, I came to Long Barn. Open the top button of your jersey and you will see, nestling inside, a lively squirrel with the most inquisitive habits, but a dear creature all the same—

Postcards dating from 1913-1914 from Franz Marc to friends and artists Erich Heckel, Else Lasker-Schüler, Wassily Kandinsky, Albert Bloch and Paul Klee

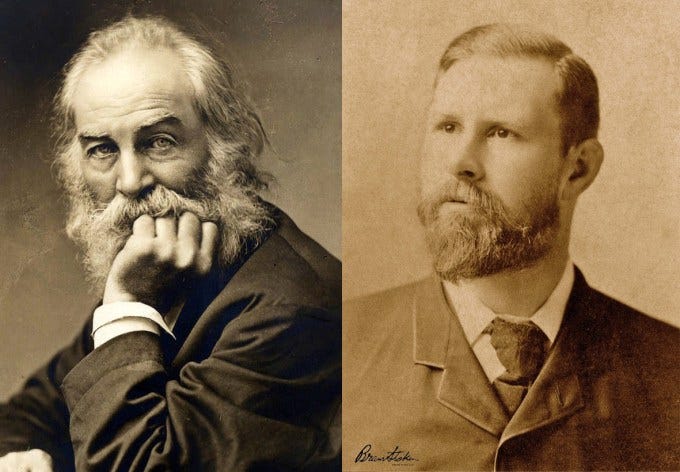

On Valentine’s Day 1876, Bram Stoker wrote an extraordinary love letter to Walt Whitman (who would’ve thought huh?)

My dear Mr. Whitman.

I hope you will not consider this letter from an utter stranger a liberty. Indeed, I hardly feel a stranger to you, nor is this the first letter that I have written to you. My friend Edward Dowden has told me often that you like new acquaintances or I should rather say friends. And as an old friend I send you an enclosure which may interest you. Four years ago I wrote the enclosed draft of a letter which I intended to copy out and send to you — it has lain in my desk since then — when I heard that you were addressed as Mr. Whitman. It speaks for itself and needs no comment. It is as truly what I wanted to say as that light is light. The four years which have elapsed have made me love your work fourfold, and I can truly say that I have ever spoken as your friend. You know what hostile criticism your work sometimes evokes here, and I wage a perpetual war with many friends on your behalf. But I am glad to say that I have been the means of making your work known to many who were scoffers at first. The years which have passed have not been uneventful to me, and I have felt and thought and suffered much in them, and I can truly say that from you I have had much pleasure and much consolation — and I do believe that your open earnest speech has not been thrown away on me or that my life and thought fail to be marked with its impress. I write this openly because I feel that with you one must be open. We have just had tonight a hot debate on your genius at the Fortnightly Club in which I had the privilege of putting forward my views — I think with success. Do not think me cheeky for writing this. I only hope we may sometime meet and I shall be able perhaps to say what I cannot write. Dowden promised to get me a copy of your new edition and I hope that for any other work which you may have you will let me always be an early subscriber. I am sorry that you’re not strong. Many of us are hoping to see you in Ireland. We had arranged to have a meeting for you. I do not know if you like getting letters. If you do I shall only be too happy to send you news of how thought goes among the men I know. With truest wishes for your health and happiness believe me

Your friend

Bram Stoker.

*

In a letter from March 6, Whitman writes to his young admirer:

BRAM STOKER, —

My dear young man, — Your letters have been most welcome to me — welcome to me as a Person and then as Author — I don’t know which most. You did so well to write to me so unconventionally, so fresh, so manly, and affectionately too. I, too, hope (though it is not probable) that we will some day personally meet each other. Meantime, I send my friendship and thanks.

Edward Dowden’s letter containing among others your subscription for a copy of my new edition has just been recd. I shall send the book very soon by express in a package to his address. I have just written to E.D.

My physique is entirely shatter’d — doubtless permanently — from paralysis and other ailments. But I am up and dress’d, and get out every day a little, live here quite lonesome, but hearty, and good spirits. — Write to me again.

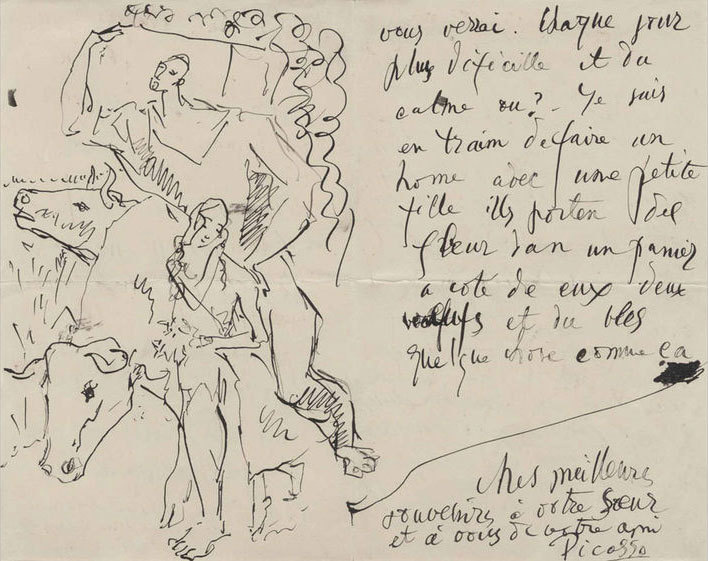

Henri Matisse’s autographed letters to his wife Amélie (“Mélo”) about his work in Tangier in 1912-1913

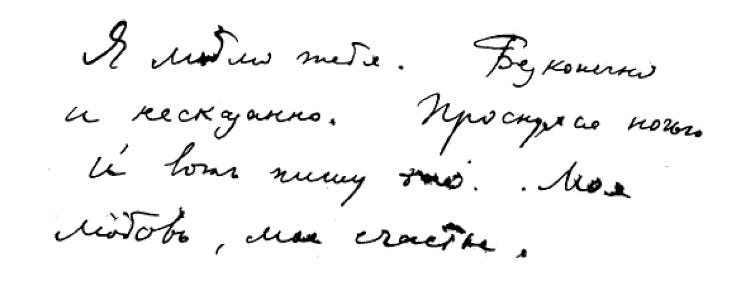

Vladimir Nabokov’s utter devotion to his wife through some excerpts from his collection Letters to Vera

My delightful, my love, my life, I don’t understand anything: how can you not be with me? I’m so infinitely used to you that I now feel myself lost and empty: without you, my soul. You turn my life into something light, amazing, rainbowed—you put a glint of happiness on everything—always different: sometimes you can be smoky-pink, downy, sometimes dark, winged—and I don’t know when I love your eyes more—when they are open or shut. It’s eleven p.m. now: I’m trying with all the force of my soul to see you through space; my thoughts plead for a heavenly visa to Berlin via air . . . My sweet excitement . . .

*

My tenderness, my happiness, what words can I write for you? How strange that although my life’s work is moving a pen over paper, I don’t know how to tell you how I love, how I desire you. Such agitation—and such divine peace: melting clouds immersed in sunshine—mounds of happiness. And I am floating with you, in you, aflame and melting—and a whole life with you is like the movement of clouds, their airy, quiet falls, their lightness and smoothness, and the heavenly variety of outline and tint—my inexplicable love. I cannot express these cirrus-cumulus sensations.

*

How can I explain to you, my happiness, my golden, wonderful happiness, how much I am all yours—with all my memories, poems, outbursts, inner whirlwinds? Or explain that I cannot write a word without hearing how you will pronounce it—and can’t recall a single trifle I’ve lived through without regret—so sharp!—that we haven’t lived through it together—whether it’s the most, the most personal, intransmissible—or only some sunset or other at the bend of a road—you see what I mean, my happiness?

*

How I wish you were saying, right now, with feeling: “But you promised me!?. . .” I love you, my sun, my life, I love your eyes—closed— all the little tails of your thoughts, your stretchy vowels, your whole soul from head to heels. I’m tired, off to bed. I love you.

From The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh

The ever steamy Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller

Nin to Miller:

Things I forgot to tell you:

That I love you and that when I awake in the morning, I use my intelligence to discover more ways of appreciating you.

That I love you.

That I love you.

That I love you.*

Miller to Nin:

“Give me a few days of peace in your arms—I need it terribly. I’m ragged, worn, exhausted. After that I can face the world.”

“Something in you pacifies me. You’ve always had that power over me – part of you pacifies, another terrifies. How do I get sick of that? I will never get sick of that.”

Letter from Georgia O'Keeffe to a friend and fellow artist Yayoi Kusama, 1955

“After seeing her paintings in this book, I wrote to her. She responded with great kindness and generosity. Her letter gave me the courage I needed to leave for New York,” said Yayoi Kusama

Finally, some bits from Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet that also doubles up as excellent advice to all of us

You are so young, all still lies ahead of you, and I should like to ask you, as best I can, dear Sir, to be patient towards all that is unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms, like books written in a foreign tongue. Do not now strive to uncover answers: they cannot be given you because you have not been able to live them. And what matters is to live everything. Live the questions for now.

*

Believe in a love that is being stored up for you like an inheritance, and have faith that in this love there is a strength and a blessing so large that you can travel as far as you wish without having to step outside it.

*

And your doubt can become a good quality if you train it. It must become knowing, it must become critical. Ask it, whenever it wants to spoil something for you, why something is ugly, demand proofs from it, test it, and you will find it perhaps bewildered and embarrassed, perhaps also protesting. But don't give in, insist on arguments, and act in this way, attentive and persistent, every single time, and the day will come when, instead of being a destroyer, it will become one of your best workers--perhaps the most intelligent of all the ones that are building at your life.

*

And for the rest, let life happen to you. Believe me: life is right, in any case.